Solitary confinement reform in the United States is at a crossroads. Once considered a necessary tool for prison management, solitary confinement is now widely condemned as a practice that inflicts profound psychological and physical harm, undermines rehabilitation, and, in many cases, violates constitutional and international human rights standards. Despite mounting evidence of its dangers and a wave of reforms, tens of thousands of people remain isolated in U.S. prisons and jails every day. This comprehensive analysis explores the history, harms, legal battles, reform efforts, and the future of solitary confinement in America, providing an in-depth thought leadership perspective for policymakers, practitioners, and advocates.

If you have a loved one in the Federal Bureau of Prisons who is in solitary confinement and you need guidance or advocacy, our team is here to help. Book an initial consultation with our federal prison experts to discuss your situation, explore your options, and get the support you need during this challenging time.

Table of Contents

What Is Solitary Confinement?

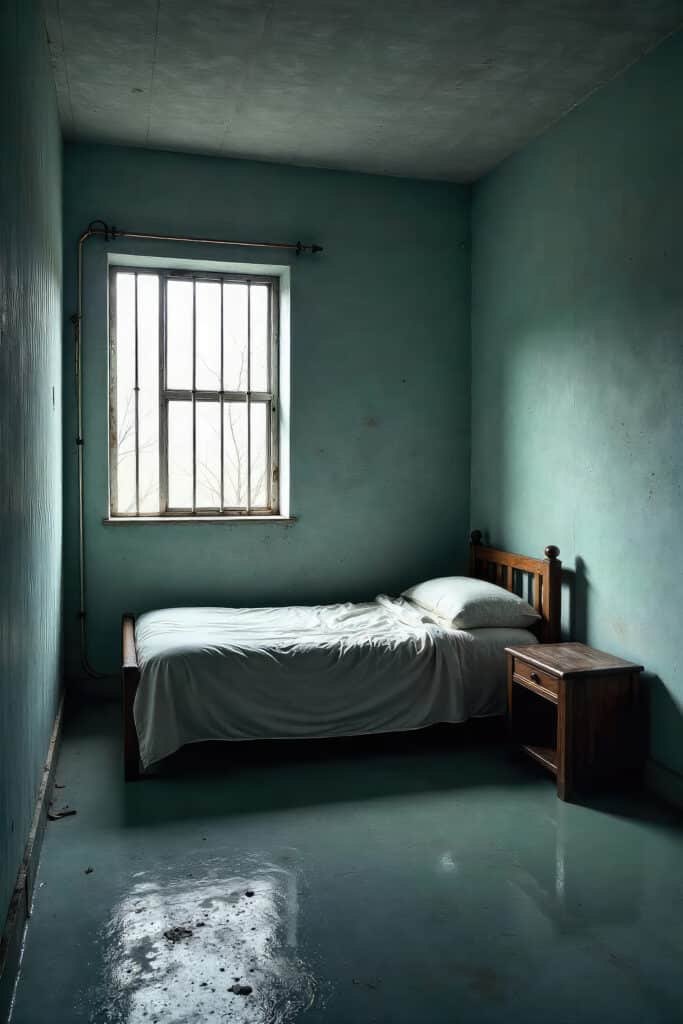

Solitary confinement—also known as “segregated housing,” “restrictive housing,” “special housing units (SHU),” or “the hole”—is the practice of isolating a prisoner in a cell for 22 to 24 hours a day, with minimal human contact and limited access to programs, property, and the outside world. Cells are typically the size of a parking space, often kept brightly lit around the clock and maintained at uncomfortable temperatures. Meals are delivered through slots in the door, and prisoners are frequently denied access to education, work, or meaningful activity.

Types of Solitary Confinement

Solitary confinement, also called restrictive housing or segregation, is not a single practice but a spectrum of policies and conditions that vary across facilities and jurisdictions. While the core feature is isolation, typically 22 to 24 hours a day in a small cell, multiple rationales and operational forms exist, each with distinct procedures, durations, and impacts.

Disciplinary Segregation

Disciplinary segregation is a formal punishment for violating prison rules or regulations. After a disciplinary infraction, such as fighting, possessing contraband, or disobeying orders, an incarcerated person may be placed in solitary confinement for a fixed period, often following a hearing before an internal disciplinary board. These hearings are supposed to provide some due process, allowing the individual to present a defense, but the process is often cursory, and outcomes are rarely overturned.

Disciplinary segregation is generally time-limited, with sentences ranging from a few days to several months, but repeated infractions can result in much longer stays. In some states, disciplinary segregation is called “punitive segregation” or “room restriction.” It is used to reinforce institutional order, as detailed in this Urban Institute report and explained elsewhere.

Administrative Segregation

Administrative segregation separates individuals deemed a threat to the safety and security of the facility, staff, or other prisoners. Placement is often based on subjective assessments by correctional officers or administrators and can be indefinite, lasting months or even years. Administrative segregation is frequently used for alleged gang members, people accused of organizing unrest, or those considered escape risks. In some cases, people are kept in administrative segregation for decades, with little transparency or recourse. This type of segregation is the most researched and controversial, as it is often imposed without clear criteria or meaningful due process.

Protective Custody

Protective custody is intended for individuals considered especially vulnerable in the general population. This includes LGBTQ+ prisoners, people with high-profile cases, informants, and those who have been threatened or assaulted. While the stated purpose is safety, protective custody often means solitary confinement under the same harsh conditions as disciplinary or administrative segregation. Many LGBTQ+ and transgender prisoners are placed in isolation “for their own protection,” but this can exacerbate trauma and mental health issues. The American Friends Service Committee notes that protective custody can be voluntary or involuntary and that prisoners may be forced to choose between isolation and risking violence from others. The National Center for Transgender Equality highlights this practice is especially damaging for transgender individuals.

Temporary Segregation

Temporary segregation, sometimes called “emergency segregation” or “short-term isolation,” immediately separates an individual from the general population, often in response to a perceived imminent threat or ongoing investigation. This type of segregation is usually initiated by supervisory staff. It may last from a few hours to several days, pending further review or transfer to another form of segregation.

Supermax and Special Management Units

Some facilities, especially “supermax” prisons, are designed almost entirely for long-term isolation. All residents may be subject to solitary-like conditions in these settings, regardless of their disciplinary or administrative status. The federal Bureau of Prisons uses terms like “Special Housing Units” (SHU) for lower-level segregation and “Special Management Units” (SMU) for more serious or long-term cases. Supermax facilities like California’s Pelican Bay, Virginia’s Red Onion, and the federal ADX Florence are notorious for holding people in near-total isolation for years, as documented by Solitary Watch and in the Urban Institute’s research.

Pretrial and Immigration Detention

Solitary confinement is also used in local jails and immigration detention centers, sometimes for people who have not been convicted of any crime. Pretrial detainees may be placed in solitary for their own protection, for alleged disciplinary issues, or simply due to overcrowding or lack of appropriate housing. In immigration detention, solitary has been used for LGBTQ+ individuals, people with mental illness, and those who report abuse—often as a form of retaliation or administrative convenience, as explored in this Journalists Resource primer.

Key Characteristics and Conditions

Regardless of the type, solitary confinement typically involves confinement behind a solid steel door for 22–24 hours a day, severely limited human contact and infrequent phone calls or visits, restricted access to rehabilitative or educational programming, sensory deprivation (including permanent lighting and minimal stimuli), and grossly inadequate medical and mental health care. Some facilities employ additional forms of physical and “no-touch” torture, such as restraint chairs, forced insomnia, and extreme temperatures, as reported by the American Friends Service Committee.

Cells are often 6×9 to 8×10 feet, with solid metal doors and meals passed through a slot. Some supermax units entirely consist of such cells, with virtually no opportunity for work, programming, or meaningful activity.

Disparities in Use

The Bureau of Justice Statistics and independent studies have found that Black and Latino prisoners are disproportionately placed in solitary. Black men born in the 1980s have an 11% lifetime risk of solitary confinement, compared to 4% for white men. This reflects broader patterns of racial disparity and raises serious civil rights concerns.

Summary Table: Types of Solitary Confinement

| Type | Purpose/Trigger | Duration | Due Process | Typical Conditions |

| Disciplinary Segregation | Rule violations | Days to months | Disciplinary hearing | Severe isolation, time-limited |

| Administrative Segregation | Perceived threat, gangs, unrest | Indefinite | Minimal/subjective | Severe isolation, can be years |

| Protective Custody | Vulnerability, safety concerns | Varies | Voluntary/involuntary | Same as other segregation |

| Temporary Segregation | Emergency, investigation | Hours to days | Supervisory review | Similar to other segregation |

| Supermax/SMU | Chronic high-risk, long-term control | Years/decades | Varies | Total isolation, no programs |

| Pretrial/Immigration | Pending trial, admin, retaliation | Varies | Minimal | Similar to above |

Solitary confinement—by any name or rationale—remains one of the most severe and controversial practices in the U.S. penal system, with mounting evidence of its psychological, physical, and social harms.

Daily Life in Solitary Confinement

Daily life in solitary confinement is marked by profound monotony, deprivation, and psychological stress. The experience is shaped by extreme isolation, sensory deprivation, and a near-total lack of meaningful human contact. Research and firsthand accounts have shown these conditions can quickly erode mental health and well-being, even in individuals with no history of psychological issues. This research further supports solitary confinement reform efforts.

The Cell and Physical Environment

Prisoners in solitary are typically confined to a small, windowless cell—often about 6 by 9 feet—for 22 to 24 hours each day. The cell usually contains only a concrete or steel bed, a toilet, and a sink. Harsh fluorescent lighting is often left on around the clock, making it difficult for prisoners to maintain a normal sleep schedule or sense of time. This constant illumination and a lack of natural light or fresh air can disrupt circadian rhythms and contribute to chronic insomnia and fatigue. Sensory deprivation and environmental monotony are core features of most solitary units.

Out-of-Cell Time and Exercise

Opportunities to leave the cell are limited. Most prisoners are allowed out for only one hour per day, and this time is typically spent alone in a small, caged exercise yard or a bare concrete enclosure. In some facilities, the “yard” is simply another cage or a slightly larger cell, offering little relief from the sense of confinement. During this hour, there is rarely access to exercise equipment, fresh air, or natural sunlight. The American Friends Service Committee reports that some prisoners may go days or weeks with no meaningful physical activity, further compounding the health risks of isolation.

Social Isolation and Human Contact

Human contact in solitary is minimal and often adversarial. Interactions with correctional officers are typically limited to brief moments during meal delivery, cell checks, or escorting to and from the exercise area. Communication with other prisoners is usually impossible, as cells are designed to prevent conversation, and communal activities are strictly prohibited. The Solitary Watch project has documented that many prisoners spend months or years without a single friendly conversation, hug, or handshake.

Access to Property, Communication, and Stimulation

Access to personal property is heavily restricted in solitary. If permitted, reading materials are limited to a few books or magazines. Television, radio, or other forms of entertainment are rare or non-existent. Phone calls are infrequent and often expensive, and visitation rights are highly restricted—sometimes limited to non-contact visits through glass partitions or denied altogether. Letters may be delayed or censored, further deepening the sense of isolation. According to Solitary Watch, these restrictions are designed to maximize control but have devastating effects on mental health.

Psychological and Physical Effects

Many prisoners describe the experience of solitary as a form of living death—an existence stripped of purpose, stimulation, and hope. The lack of sensory input and social interaction can quickly erode mental health, leading to anxiety, depression, panic attacks, hallucinations, and cognitive impairments. Some individuals develop hypersensitivity to noise or light, while others experience emotional numbness or uncontrollable rage. The Urban Institute notes that even short periods in solitary can cause lasting trauma, with the risk of suicide several times higher among those in segregation compared to the general prison population.

Sleep, Time, and the Erosion of Identity

Sleep disturbances are prevalent in solitary confinement, often caused by constant lighting, lack of natural cues, and the ever-present stress of confinement. Many prisoners report chronic insomnia, nightmares, and difficulty distinguishing between day and night. Over time, the monotony and deprivation of solitary can erode a person’s sense of self, leading to what some survivors describe as “social death.” The cumulative impact of these conditions has led many experts and human rights organizations to describe solitary confinement as a form of psychological torture, as highlighted by both Solitary Watch and the Urban Institute.

A Brief History: From Quaker Experiment to Mass Incarceration Tool

The origins of solitary confinement in America are rooted in the reformist impulses of the 18th and 19th centuries. Quaker reformers in Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail believed isolation and reflection would lead to penitence and moral improvement. This approach was institutionalized in 1829 at Eastern State Penitentiary, where prisoners lived in near-total isolation, each in their own cell with a Bible.

Early Failures and the Supreme Court’s Warning

The results were disastrous. By the 1830s, reports documented high rates of insanity, suicide, and physical deterioration among isolated prisoners. Charles Dickens, after visiting Eastern State, wrote that “solitary confinement is worse than any torture of the body.” French observers Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont concluded that solitary “destroys the criminal without intermission…it does not reform, it kills.” By the late 19th century, the U.S. Supreme Court in In re Medley, 134 U.S. 160, recognized the practice’s devastating effects, noting that extended solitary confinement led to “semi-fatuous conditions” and violent insanity.

The Supermax Era and Modern Expansion

Despite these warnings, solitary confinement re-emerged in the late 20th century, driven by the “tough on crime” policies of the 1980s and 1990s. The 1983 Marion Federal Prison lockdown marked the birth of the modern supermax prison, with prisoners held in permanent isolation. By 2000, over 44,000 prisoners were held in supermax facilities. The supermax model became the default for managing perceived threats, often with little oversight or external accountability.

The Shift Toward Solitary Confinement Reform

Public outcry, litigation, and research have led to a reevaluation of solitary’s role. High-profile hunger strikes, such as those at Pelican Bay, and investigative journalism by outlets like The Marshall Project have exposed the practice’s harms and catalyzed legislative and policy changes in several states. The United Nations’ Mandela Rules (2015) now prohibit solitary beyond 15 days and have influenced U.S. reform.

The Human Cost: Anthony Gay and the Reality of Isolation

Solitary confinement’s devastating impact is most powerfully illustrated by the lived experiences of those subjected to it. Among the most harrowing and instructive stories is that of Anthony Gay, whose journey through the extremes of isolation highlights both the personal and systemic failures of the U.S. correctional system. His story has spurred many solitary confinement reform efforts.

Anthony Gay’s Descent into Solitary

Anthony Gay was convicted at age 19 for a minor robbery—an offense involving the theft of a single dollar and a baseball cap. Suffering from untreated mental illness, Gay entered the Illinois prison system, where, instead of receiving psychiatric care, he was placed in solitary confinement. The isolation quickly exacerbated his mental health struggles. In a desperate attempt to get help, Gay began engaging in self-harm and disruptive behavior, hoping to draw the attention of medical staff. Instead, these actions led to further disciplinary charges and extended his time in solitary.

Over the course of 24 years, Anthony Gay spent more than 8,000 days in isolation. He mutilated himself hundreds of times, cutting his arms, neck, and even his genitals and stuffing foreign objects into his wounds. He once packed a fan motor into a gash in his leg; on another, he hung a piece of his testicle on his cell door. These acts were cries for help and a response to the overwhelming psychological pain of isolation. His ordeal is detailed in a Chicago Tribune profile, which underscores the extremity of his suffering, the system’s failure to intervene, and the emergency nature of solitary confinement reform.

Medical Neglect and Litigation

Despite the clear signs of severe mental illness, prison medical staff frequently dismissed Gay as a manipulator rather than a patient in crisis. He was denied psychotropic medication and, instead of being offered therapy or psychiatric intervention, was subjected to extreme restraint—sometimes shackled for over 32 hours at a time on a steel bunk in a cold cell, with minimal clothing. This punitive approach to mental illness is documented in Gay v. Chandra, 652 F. Supp. 2d 959 (S.D. Ill., 2009), where the court record reveals a pattern of medical neglect and cruel treatment.

Supported by legal advocates, including the Uptown People’s Law Center and the MacArthur Justice Center, Gay challenged his conditions of confinement and the extension of his sentence, which ballooned from seven years to 97 years due to disciplinary infractions incurred in solitary. After years of litigation and public advocacy, his sentence was reduced, and he was released in 2018. Gay is now pursuing a lawsuit against the State of Illinois, alleging violations of his Eighth Amendment rights and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Other Personal Accounts

Anthony Gay’s experience, while extreme, is far from unique. The Voices from Solitary project, curated by Solitary Watch, has collected hundreds of first-person narratives from people who have endured years or even decades in isolation. These accounts consistently describe a world of hallucinations, compulsive self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and the gradual erosion of hope and identity. Many survivors of solitary report lasting psychological scars, including chronic depression, anxiety, paranoia, and difficulty adjusting to life outside prison. For some, the trauma is so severe that they cannot maintain employment, relationships, or stable housing after release.

A 2023 study by the Urban Institute found that even short periods in solitary can lead to long-term mental health consequences, and the risk of suicide is several times higher among those in segregation compared to the general prison population.

The Ripple Effect: Families and Communities

The impact of solitary confinement extends well beyond the individual. Families of those in isolation often struggle to maintain contact due to restrictive visitation policies, expensive phone calls, and the emotional toll of witnessing a loved one’s decline. According to a report by the Prison Policy Initiative, people released directly from solitary are more likely to become homeless or re-offend, contributing to cycles of instability and incarceration in their communities.

Children of incarcerated parents, especially those in solitary confinement, are at heightened risk for trauma, anxiety, and academic difficulties. Research shows that children of isolated parents face a fourfold increase in their own risk of future incarceration. Moreover, 85% of families report that their contact with loved ones in solitary confinement is severely restricted, leading to widespread anxiety and depression among family members.

At the community level, the ripple effects include higher rates of recidivism, unemployment, and untreated mental illness among those released from solitary. The burden of these outcomes is disproportionately borne by communities of color, which are already overrepresented in the nation’s prisons and jails.

The Science: Psychological and Physical Harms

The devastating harms of solitary confinement are not speculative—they are confirmed by decades of research in psychology, neuroscience, and public health. Clinical studies, neuroimaging, and large-scale epidemiological research have established that isolation inflicts profound and lasting damage on the mind and body.

The Psychological Toll

Solitary confinement triggers profound neurobiological and psychological changes. For example, MRI studies led by neuroscientist Huda Akil and published in Daedalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, have shown that even 30 days of isolation can shrink the hippocampus by 20–25%, impairing memory, learning, and spatial reasoning. Simultaneously, the amygdala—responsible for processing fear and anxiety—becomes hyperactive, making individuals more prone to stress, paranoia, and emotional dysregulation.

Chronic stress hormones, such as cortisol, are released in excess during isolation, causing hippocampal atrophy and amygdala hypertrophy. These neurobiological changes are linked to increased rates of depression, aggression, and suicidal ideation, as detailed in Daedalus.

Dr. Stuart Grassian, a former Harvard Medical School faculty member and leading psychiatrist, identified a distinct syndrome—now widely known as “SHU Syndrome”—in people subjected to prolonged solitary confinement. Symptoms include hallucinations, paranoia, hypersensitivity to external stimuli, cognitive dysfunction, and uncontrollable rage or panic attacks. Similarly, Dr. Terry Kupers has documented in the Transformative Studies Institute journal that even psychologically healthy individuals can develop psychosis, mania, or compulsive self-harm when isolated.

The 2023 meta-analysis by the Urban Institute of 194,078 incarcerated individuals found that solitary confinement increases recidivism by 67% and homicide risk by 54%, with the most severe effects seen in those isolated for more than 14 days. The longer the isolation, the greater the risk of lasting psychological harm. For this reason, solitary confinement reform is critical for both short- and long-term placements.

Effects on Vulnerable Populations

Certain groups are especially at risk for the harms of solitary confinement. Women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people with disabilities face unique vulnerabilities:

- Women in solitary are more likely to have histories of trauma and mental illness and are at increased risk for self-harm and suicide. Pregnant women in isolation face triple the risk of preterm birth and other complications, as reported by The Marshall Project.

- Black and Latino prisoners are disproportionately subjected to solitary; Bureau of Justice Statistics data shows Black people make up 45% of those in solitary, compared to 33% of the general prison population.

- Transgender prisoners are 85% more likely to be placed in solitary “for their own protection,” a practice that the National Center for Transgender Equality has found exacerbates trauma, depression, and suicidal ideation.

- People with disabilities, especially those with serious mental illness or cognitive impairments, are often placed in solitary because they are perceived as disruptive or difficult to manage, even though isolation worsens their conditions. This is highlighted in coverage by Solitary Watch.

Physical Effects on the Brain and Body

The physical consequences of solitary confinement are equally alarming. Social isolation and chronic stress accelerate cardiovascular deterioration. According to the Urban Institute, individuals in solitary are 31% more likely to develop hypertension than those in the general prison population, increasing their risk of stroke and heart disease.

A 2019 study published in The Lancet Public Health found that post-release mortality rates are 24% higher for people who experienced solitary confinement, with the risk of opioid overdose death spiking by 127% in the first two weeks after release. The authors attribute these outcomes to a combination of psychological distress, loss of tolerance, and lack of support.

Long-term solitary confinement also correlates with asymmetric hippocampal atrophy—a pattern seen in Alzheimer’s patients—leading to cognitive decline, memory loss, and difficulties with emotional regulation, as described in Daedalus. Other physical effects include insomnia, digestive problems, weakened immune response, and chronic pain due to inactivity and stress.

Lasting Impact and Cumulative Harm

The cumulative impact of solitary confinement is profound. Even after release, survivors often struggle with persistent anxiety, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Many report difficulty reintegrating into society, maintaining relationships, or holding down employment. The risk of homelessness and recidivism is significantly higher for those who have spent time in solitary.

The scientific consensus—reflected by Solitary Watch, the Urban Institute, and a growing body of peer-reviewed research—is clear: solitary confinement inflicts lasting psychological and physical harm, with especially severe consequences for vulnerable populations. These findings have fueled calls for reform and led many experts and human rights organizations to label prolonged isolation as a form of psychological torture, necessitating solitary confinement reform.

Suicide Rates in Solitary Confinement

The connection between solitary confinement and suicide is stark and well-documented. Although less than ten percent of the prison population is held in solitary or restrictive housing, this small group accounts for a disproportionately high share of suicides and self-harm incidents.

Disproportionate Suicide and Self-Harm Rates

Research consistently shows that prisoners in solitary confinement are at dramatically increased risk of suicide and self-harm. For example, a 2021 report from Brooklyn Defender Services found that the suicide rate in solitary units in New York State prisons was ten times the overall national prison suicide rate. From 2015 to 2019, the rate of suicides in solitary confinement was over five times higher than in the rest of the New York prison system. In 2019 alone, at least one-third of suicides in New York prisons took place in solitary confinement, with suicide attempts in these units occurring at a rate twelve times higher than in the general prison population.

A Times Union investigation revealed that, of 688 suicide attempts in New York prisons between January 2015 and April 2019, 43 percent occurred in solitary confinement units. Many incarcerated people report that fear of being returned to solitary after expressing mental health distress leads them to hide their symptoms, compounding the risk.

California’s experience is similarly dire. In 2004, 73 percent of all suicides in California prisons occurred in isolation units, despite these units housing less than ten percent of the state’s total prison population. By 2005, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation reported a suicide rate of 27 deaths per 100,000 prisoners—nearly double the national prison suicide rate and more than twice the rate in the general community. Many of these deaths were deemed foreseeable or preventable by court monitors and mental health experts, who cited the role of extreme isolation and lack of timely intervention.

Indiana, too, has seen a suicide rate in segregation units nearly three times that of traditional housing, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting an age-adjusted suicide rate of 16.4 per 100,000 in 2022—a 35.5% increase over the past two decades. The risk is especially acute for young adults and those with serious mental illness.

Solitary Confinement and Self-Harm

The risk of self-harm is also sharply elevated in solitary. A study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that inmates punished by solitary confinement were nearly seven times as likely to commit acts of self-harm compared to those never placed in isolation, even after controlling for factors like length of stay, mental illness, age, and race. The study also found that both serious mental illness and being under age 18 were strong predictors of self-harm. Still, the risk associated with solitary was even higher—indicating that isolation itself is a primary driver of self-injury and suicide attempts.

The Death Row Effect

The psychological toll of long-term isolation is perhaps most visible on death row. Psychiatrist Dr. Terry Kupers has documented that when states began housing condemned prisoners in solitary, the number of prisoners abandoning their appeals and asking for execution rose sharply. This phenomenon, sometimes called the “death row effect,” highlights the extreme psychological distress caused by prolonged isolation, as prisoners may come to prefer death over continued existence in solitary.

Case Example: Kalief Browder

The tragic story of Kalief Browder brought national attention to the link between solitary confinement and suicide. Browder, a teenager held at Rikers Island for three years without trial—two in solitary—died by suicide after his release. His ordeal, chronicled in The New Yorker, symbolized the system’s failure and galvanized reform efforts in New York and beyond. Browder’s case underscores how the trauma of solitary can persist long after release, especially for young people and those with preexisting mental health vulnerabilities.

The Staying Power of Solitary Confinement

Solitary confinement’s persistence in the United States is deeply rooted in institutional culture, bureaucratic inertia, and the perceived necessity of maintaining control in often chaotic and dangerous prison environments. Despite overwhelming evidence of the severe psychological and physical harm caused by prolonged isolation, the practice remains a default tool for prison administrators and correctional staff.

Institutional Inertia and Staff Culture

Keramet Reiter, a professor of law at the University of California, Irvine and author of 23/7: Pelican Bay and the Rise of Long-Term Solitary Confinement, argues that the regular use of solitary confinement is driven by path-dependency and bureaucratic routine. In her analysis, isolation has become an unremarkable and ordinary part of prison management, used not only for individuals deemed dangerous but also for those with mental illness, those needing protection, or those who simply “don’t fit” elsewhere in the system.

Staff culture within correctional facilities is a significant barrier to reform. Correctional officers’ unions often resist changes to solitary confinement policies, asserting that isolation is essential for maintaining safety and order. For example, the Corrections Officers’ Benevolent Association in New York has been vocal in opposing restrictions on solitary confinement reform, framing such reforms as threats to officer safety and institutional security. This resistance is echoed in other states, where union leaders frequently argue that eliminating or reducing solitary would endanger both staff and prisoners, despite research showing that reforms can reduce violence.

Resistance and Solitary Confinement Reform from Within

Not all correctional leaders oppose solitary confinement reform. Rick Raemisch, former director of the Colorado Department of Corrections, became a national advocate for ending long-term solitary confinement after experiencing a night in isolation. In his New York Times op-ed, Raemisch described the inhumanity of solitary and led Colorado to virtually eliminate prolonged isolation, replacing it with step-down programs and mental health units. His leadership demonstrates that change is possible when correctional officials embrace reform with vision and commitment.

Other reform-minded officials and advocates continue to push for alternatives to solitary confinement, emphasizing evidence-based approaches that prioritize mental health, rehabilitation, and human dignity. Their efforts show that institutional inertia is formidable but not insurmountable when leadership, data, and public pressure align.

Solitary Confinement and the Eighth Amendment

Solitary confinement in the United States has increasingly come under judicial scrutiny, with courts examining whether its use violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. As scientific evidence of harm mounts, legal challenges have become more frequent and successful, reshaping the landscape of prison law and policy.

Key Legal Precedents

The Eighth Amendment, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishments,” has served as the constitutional foundation for many challenges to solitary confinement. Courts have begun to recognize that prolonged isolation can inflict serious psychological and physical harm, potentially rising to the level of unconstitutional punishment.

A pivotal ruling came in Porter v. Clarke, where the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the practice of keeping death row prisoners in near-permanent solitary confinement created a substantial risk of serious psychological harm and could violate the Eighth Amendment. In Porter v. Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, the Third Circuit found that decades in isolation may constitute cruel and unusual punishment, especially when it leads to significant mental deterioration.

The “Deliberate Indifference” Standard

For a successful Eighth Amendment claim, plaintiffs must typically show that prison officials acted with “deliberate indifference” to a substantial risk of serious harm. This standard, established by the Supreme Court in Farmer v. Brennan, requires evidence that officials were aware of and disregarded excessive risks to inmate health or safety. In the solitary confinement context, this often means demonstrating that prison authorities knew about the well-documented psychological and physical harms of isolation but failed to take corrective action or provide alternatives.

Courts increasingly rely on expert testimony and scientific research to determine whether solitary confinement poses such risks, and the growing body of evidence has made it harder for prison officials to claim ignorance or necessity.

Recent Litigation Trends

There has been a surge in class-action lawsuits and individual claims challenging the constitutionality of prolonged solitary confinement in recent years. In several states, including Connecticut, Virginia, and New York, courts have ordered sweeping changes, such as strict time limits, mandatory mental health assessments, and regular reviews for those in isolation.

A landmark case reported by the ABA Journal in 2024 saw a New York jury find that nine years of solitary confinement violated the Eighth Amendment, resulting in substantial damages for the plaintiff. These cases reflect a growing judicial consensus that indefinite or excessive use of solitary can amount to unconstitutional punishment, particularly for vulnerable populations such as those with mental illness or juveniles.

International Human Rights Law

International human rights law also strongly condemns the use of solitary confinement. The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules) explicitly prohibit the use of solitary confinement for more than 15 consecutive days, recognizing that longer periods constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

The Convention Against Torture further obligates signatory states, including the United States, to prevent practices that amount to torture or inhuman treatment. The United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on Torture has called for an absolute ban on solitary for juveniles and people with mental disabilities, emphasizing that prolonged isolation can amount to torture under international law.

While the U.S. has not fully adopted these standards into domestic law, international criticism has spurred advocacy and solitary confinement reform efforts. Many states and federal agencies now cite the Mandela Rules and UN guidance in developing new policies and limiting the use of solitary confinement.

Juvenile Solitary Confinement: The Push for Reform

Solitary confinement’s impact on juveniles is especially devastating, and a growing consensus among scientists, legal experts, and policymakers now recognizes that isolation is fundamentally incompatible with the developmental needs and rights of young people.

Legal and Scientific Consensus

Adolescents’ brains are still developing, particularly in areas related to impulse control, emotional regulation, and decision-making. Research from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the National Academies of Sciences demonstrates that solitary confinement can cause or exacerbate mental illness, impede rehabilitation, and significantly increase the risk of suicide among youth. The United Nations and international human rights organizations have called for a total ban on solitary for anyone under 18, labeling it cruel and inhuman treatment.

Despite this scientific and legal consensus, 11 states—including Alabama, Mississippi, and Wyoming—still permit unrestricted solitary confinement for juveniles. Neuroscience confirms that isolation during adolescence disrupts prefrontal cortex development, increasing the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and aggression, as summarized in recent developmental impact research.

The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that “children are constitutionally different from adults for purposes of sentencing,” a principle established in Miller v. Alabama, Graham v. Florida, and Roper v. Simmons. While these cases did not directly address solitary confinement, their reasoning has influenced lower court rulings and legislative reforms that increasingly treat juvenile isolation as constitutionally suspect.

Federal and State Reforms

At the federal level, the First Step Act prohibits solitary confinement for juveniles in federal custody except as a temporary response to immediate threats, and even then, for no more than three hours. At least 21 states—including California, New York, and Massachusetts—have enacted bans or strict limits on juvenile solitary confinement, sharply restricting or eliminating the practice for minors.

States like Connecticut and Illinois have implemented reforms after litigation and advocacy revealed the disproportionate use of solitary on youth of color and those with disabilities. The Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI) has become a national model, promoting alternatives such as behavioral interventions, counseling, and family engagement. Minnesota’s 2023 solitary confinement reforms now require annual reporting of isolation durations and injuries, while Louisiana bans solitary confinement except for immediate threats.

Ongoing Litigation and Advocacy

Despite progress, some states and localities continue to use solitary for youth, often under different names or in response to staffing shortages. Litigation remains a crucial tool for solitary confinement reform. The Southern Poverty Law Center and other groups have successfully challenged juvenile solitary in Florida and elsewhere, citing Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment violations. Florida’s 2019 lawsuit revealed 11,378 isolation incidents in a single year among juveniles.

Advocacy organizations such as the Youth First Initiative and Campaign for Youth Justice continue to push for complete abolition, emphasizing the stories of youth survivors and the long-term costs to society. The suicide of Kalief Browder after two years in Rikers’ solitary confinement—while he awaited trial as a teenager—spurred New York City’s 2015 ban on solitary for detainees under 21.

Solitary Confinement Reforms Across the States: Progress and Setbacks

Solitary confinement reform has gained momentum across the United States, but the pace and scope of change vary dramatically by state, county, and individual facility. Some states have embraced evidence-based alternatives and robust oversight, while others have resisted or circumvented reform efforts.

Colorado: A Model for Comprehensive Reform

Colorado is widely recognized as a national leader in solitary confinement reform. Following lawsuits, public scandals, and the high-profile murder of corrections director Tom Clements by a recently released solitary prisoner, the state undertook sweeping changes. Under the leadership of Rick Raemisch, Colorado closed its notorious all-solitary supermax facility and implemented policies to keep prisoners with major mental illnesses out of administrative segregation.

The state also introduced step-down programs that provide gradual reintegration, mental health support, and at least four hours of out-of-cell time daily. According to the Colorado Department of Corrections, these reforms resulted in a 90% reduction in using solitary and a 40% drop in prison violence. The state also reported improved recidivism rates and millions of dollars in cost savings.

New Jersey: Legislative Limits and Vulnerable Populations

New Jersey’s Isolated Confinement Restrictions Act is among the most progressive solitary reforms in the country. The law caps solitary at 20 consecutive days and bans it outright for vulnerable populations, including juveniles, pregnant women, and individuals with mental illness. It also mandates regular mental health assessments and due process protections for anyone in restrictive housing. While implementation has faced challenges, New Jersey’s model is frequently cited by advocates as a legislative best practice.

Illinois: County-Level Innovation in Cook County

In Cook County, Illinois, Sheriff Tom Dart eliminated solitary confinement in the Chicago jail, replacing it with a Special Management Unit (SMU) emphasizing programming, therapy, and socialization. Dart’s reforms have been credited with reducing violence and improving outcomes for both staff and detainees. The Cook County model demonstrates how local leadership can drive change even without statewide solitary confinement reform.

Massachusetts: Progress and Bureaucratic Resistance

Massachusetts enacted the Criminal Justice Reform Act (CJRA), which established due process protections and humane conditions for prisoners in restricted housing. However, the state’s Department of Correction has sometimes circumvented these reforms by renaming isolation units or creating new categories of restrictive housing. According to WBUR, this illustrates the ongoing need for vigilant oversight and enforcement to ensure that bureaucratic workarounds do not undermine reforms.

California: Litigation-Driven Change

California’s experience is a cautionary tale of both excess and reform. For decades, thousands of prisoners were held in indefinite solitary based on gang affiliation, often for years or even decades. Hunger strikes—some involving over 30,000 prisoners—drew global attention to the issue. The resulting Ashker v. Brown settlement ended indefinite solitary, eliminated gang affiliation as a basis for isolation, and created step-down programs for reintegration. The number of prisoners in long-term isolation dropped by over 90%, and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation reported annual savings of $60 million by reducing solitary use.

New York: Statutory and Court-Ordered Reform

In New York, a class-action lawsuit led to Peoples v. Fischer, which resulted in reduced isolation sentences, improved conditions, and the creation of alternative programs. The HALT Solitary Confinement Act, passed in 2021, limits solitary to 15 days and bans it for vulnerable groups, including people with disabilities and those under 21. The law also mandates regular mental health assessments and increased transparency.

Georgia: Settlement-Driven Limits

Georgia’s settlement in Gumm v. Ford imposed a two-year cap on isolation, mandated increased out-of-cell time, and required regular mental health assessments. This case, brought by the Southern Center for Human Rights, demonstrates how litigation can drive significant improvements even in states with a history of harsh solitary practices.

Connecticut: Comprehensive Legislative Reform

Connecticut passed the PROTECT Act (Public Act No. 21-53) in 2021, which strictly limits solitary confinement, mandates daily out-of-cell time, and requires independent oversight. The law prohibits solitary for more than 15 consecutive days and bans its use for vulnerable populations. Connecticut’s reforms are seen as a model for balancing security concerns with human rights.

Nebraska: Transparency and Oversight

Nebraska has tried to increase transparency around solitary confinement usage. The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services publishes regular reports on restrictive housing and has implemented a review process to ensure that prisoners are not held in isolation longer than necessary. While challenges remain, Nebraska’s solitary confinement reform approach has reduced the number of people in long-term solitary.

Maine: Early Adopter of Reform

Maine was one of the first states to reduce the use of solitary confinement dramatically. Under the leadership of former corrections commissioner Joseph Ponte, Maine cut its solitary population by over 70% between 2011 and 2014. The state implemented alternatives such as step-down units, increased mental health care, and individualized behavior plans.

States Resisting Change: Indiana and Texas

Despite progress elsewhere, some states remain resistant to solitary confinement reform. Indiana continues to hold many prisoners in solitary confinement, often by rebranding isolation units or creating new categories of restrictive housing. Investigations by The Appeal have found that Indiana’s Department of Correction has been slow to implement meaningful oversight or alternatives.

Texas holds more prisoners in long-term isolation than any other state, with over 4,400 people in solitary—many for decades. According to the Texas Observer, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice has resisted calls for solitary confinement reform, citing security concerns and gang violence. Litigation and advocacy continue but entrenched bureaucratic culture and political resistance slow progress.

Additional States: Progress and Ongoing Challenges

- Virginia: After a 2019 settlement, Virginia agreed to end the use of long-term solitary in its Red Onion and Wallens Ridge prisons, implementing step-down programs and increasing out-of-cell time.

- Washington: The state’s Department of Corrections has piloted alternatives to solitary confinement, including mental health treatment units and incentive-based behavior programs, resulting in a significant reduction in self-harm and violence.

- Louisiana: In 2023, Louisiana adopted new rules restricting solitary for juveniles to immediate threats only, reflecting a broader trend toward limiting isolation for youth.

The Federal Landscape: Legislation and Litigation

While some states have led the way in solitary confinement reform, federal policy and practice have historically lagged behind. However, recent years have brought significant legislative proposals and landmark court rulings that are beginning to reshape the federal approach to solitary confinement.

Congressional Efforts

Several bills have been introduced in Congress to address the use of solitary confinement in federal facilities. The Solitary Confinement Reform Act, championed by Senators Dick Durbin and Chris Coons, seeks to limit the use of solitary confinement to the briefest terms possible, improve access to mental health care, and prohibit the placement of LGBTQ+ individuals in solitary “for their own protection.” The bill would require regular reviews of all placements in restrictive housing, mandate out-of-cell time, and establish clear reporting requirements to increase transparency.

Another major proposal, the End Solitary Confinement Act, would abolish the use of solitary confinement in federal prisons, jails, and detention centers, except for rare, brief periods of emergency de-escalation. The Act would also create independent oversight mechanisms to monitor compliance and investigate abuse complaints.

The First Step Act, signed into law in 2018, includes important provisions for juveniles and pregnant women in federal custody, such as banning solitary confinement for juveniles except in cases of immediate risk and prohibiting the shackling of pregnant women. However, the law does not cap the use of solitary for adults, and advocates continue to push for stronger federal legislation to align with international human rights standards.

In 2023, a new version of the Solitary Confinement Reform Act was introduced, which would ban isolation for LGBTQ+ individuals, limit stays in solitary to 15 days, and create a Civil Rights Ombudsman role to oversee compliance and investigate complaints. The End Solitary Confinement Act continues to be a focal point for national advocacy groups seeking to abolish federal solitary confinement except in the most exceptional circumstances.

Recent Litigation Outcomes

Federal courts are increasingly recognizing that prolonged solitary confinement can violate the Eighth Amendment, particularly for vulnerable populations such as those with mental illness or juveniles. In a landmark 2024 case reported by the ABA Journal, a New York jury found that nine years of solitary confinement constituted cruel and unusual punishment, awarding substantial damages to the plaintiff. This case set a powerful precedent for future litigation.

Other important decisions include Porter v. Clarke, in which the Fourth Circuit held that the use of indefinite solitary confinement on Virginia’s death row violated the Eighth Amendment, and Reynolds v. Arnone, where a federal court in Connecticut ordered sweeping changes to the state’s use of solitary, including strict time limits, mental health assessments, and regular reviews for those placed in isolation.

These rulings and growing scientific consensus about the harms of solitary are driving a wave of litigation and policy change at the federal level. As more courts recognize the constitutional and human rights implications of prolonged isolation, the pressure continues to mount for Congress and federal agencies to enact meaningful, nationwide solitary confinement reform.

The Cost and Ineffectiveness of Solitary Confinement

Despite its widespread use, solitary confinement is both financially burdensome and counterproductive to public safety. A growing body of research and real-world experience demonstrates that the practice drains resources, fails to deter violence, and increases recidivism and harm to both individuals and communities.

Fiscal Impact

Solitary confinement is dramatically more expensive than housing prisoners in the general population. According to the Urban Institute, the annual cost of keeping a person in solitary can be up to three times higher than in standard prison units due to the need for additional staff, enhanced security infrastructure, and specialized facilities. For example, California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office found that housing a prisoner in solitary costs approximately $75,000 per year, compared to $25,000 for the general population.

When California implemented reforms that reduced the use of solitary after the Ashker v. Brown settlement, the state saved tens of millions of dollars annually. As the Vera Institute of Justice documented, these savings were redirected toward mental health care, programming, and reentry support.

Private prison companies, such as CoreCivic and GEO Group, have also profited from solitary, charging as much as $200 per day for each cell. This financial incentive has led to concerns that the use of solitary is sometimes driven by profit motives rather than legitimate safety needs.

Public Safety and Recidivism

Contrary to claims by some corrections officials that solitary is necessary for institutional safety and order, research shows it does not reduce violence and may make prisons more dangerous. After Colorado reduced its use of solitary by 90%, the state saw a dramatic drop in assaults on staff and other prisoners, as reported by the Colorado Department of Corrections.

Solitary confinement is also strongly linked to increased recidivism and adverse post-release outcomes. According to the National Institute of Justice and the Prison Policy Initiative, individuals released directly from solitary confinement are significantly more likely to re-offend, become homeless, or experience mental health crises. A 2020 study of 229,274 North Carolina inmates found that exposure to solitary confinement doubled the risk of opioid overdose death after release.

Additional research published in the American Journal of Public Health found that solitary confinement increases reincarceration rates by 46%, and released individuals are 78% more likely to die by suicide compared to those who served their sentences in the general population.

The Myth of Deterrence

Despite longstanding claims that solitary confinement deters violence and maintains institutional order, empirical studies consistently find no correlation between isolation and lower rates of in-prison assaults or infractions. Overuse of solitary can destabilize prison environments by increasing mental health crises, suicide attempts, and staff burnout, as explained in this analysis by the Vera Institute.

A 2016 report by the Bureau of Justice Assistance concluded that solitary confinement does not reduce misconduct or violence and may exacerbate behavioral problems, making it harder for prisoners to reintegrate into society.

Alternatives to Solitary Confinement

The movement to reform solitary confinement is not just about ending a harmful practice—it is about building a safer, more humane, and more effective correctional system. Across the United States and internationally, states, counties, and prison systems are experimenting with a range of alternatives that prioritize rehabilitation, mental health, and community safety.

Step-Down and Incentive-Based Programs

Step-down programs are structured systems that gradually reintegrate prisoners from high-security or restrictive housing into the general population. These programs typically combine increased privileges, access to programming, and opportunities for social interaction as prisoners demonstrate positive behavior and progress through various phases. For example, the Federal Bureau of Prisons operates Reintegration Housing Units (RHUs) where prisoners can earn their way back to less restrictive settings through compliance and participation.

Incentive-based systems, such as those piloted in Santa Clara County, California, reward positive behavior with small privileges—like additional recreation time or access to preferred activities—reducing the need for punitive isolation. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, these programs have been shown to reduce violence and improve outcomes for both staff and prisoners.

Washington State has gone even further, mandating more than four hours of daily out-of-cell programming for prisoners previously held in solitary. This shift resulted in a 72% reduction in self-harm and significant improvements in institutional safety.

Restorative Justice and Mediation Programs

Restorative justice programs are gaining traction as effective alternatives to solitary confinement. These approaches focus on mediation, conflict resolution, and accountability—bringing together prisoners, victims, and sometimes staff to address harm and promote healing. In Oregon, restorative justice initiatives have reduced solitary placements by 62%. A study by the Urban Institute found that 88% of participants reported increased empathy and disciplinary incidents fell by 40%. These programs emphasize community reintegration and have been shown to reduce violence, improve prison culture, and lower recidivism rates.

Mental Health and Trauma-Informed Care

Many individuals placed in solitary suffer from untreated mental illness or trauma. Instead of isolation, some states have invested in mental health treatment units that provide trauma-informed care, counseling, group therapy, and psychiatric support. In Washington State, a 600-bed treatment facility replaced isolation units and achieved a 72% reduction in self-harm incidents, along with significant cost savings. These units address the root causes of behavioral issues, offering individualized plans and support rather than punitive segregation.

The American Psychological Association and the National Commission on Correctional Health Care recommend trauma-informed approaches and regular mental health assessments as best practices for correctional systems seeking to reduce the use of solitary.

International Inspiration: The Norwegian Model

Norway’s prison system is frequently cited as a global model for humane corrections. Facilities like Bastøy Prison emphasize normalization, where prisoners wear civilian clothes, cook their own meals, and participate in vocational training and education. The Norwegian concept of “dynamic security” prioritizes positive staff-prisoner relationships and shared activities rather than reliance on physical barriers or punitive isolation.

This approach has led to an 89% reduction in violence and a recidivism rate of just 16%, compared to 68% in the United States. The University of California, San Francisco, highlights Norway’s model as a blueprint for U.S. reformers, demonstrating that humane conditions can coexist with safety and accountability.

Additional Alternatives: Peer Support and Family Engagement

Some systems are experimenting with peer support programs, where trained prisoners assist others in crisis or help mediate disputes, reducing the need for isolation. Family engagement initiatives—such as increased visitation, family therapy, and reentry planning—have also decreased disciplinary problems and supported successful reintegration.

Ongoing Challenges and the Path Forward

While solitary confinement reform has made significant strides in many states and at the federal level, persistent obstacles and new forms of resistance continue to hinder the realization of truly humane correctional practices. The path forward requires vigilance, transparency, and a commitment to cultural and structural change.

Bureaucratic Evasion and Correctional Culture

One of the most stubborn challenges to solitary reform is bureaucratic evasion. Correctional agencies have responded to new laws or court orders in several states by rebranding or reclassifying isolation units, continuing the practice under different names. For instance, as documented by The Appeal, Indiana has renamed solitary units “restrictive housing” or “administrative separation” to skirt legal definitions and maintain the status quo. This phenomenon is not unique to Indiana—Montana, Florida, and Georgia have all faced lawsuits challenging the conditions and duration of solitary, often in the face of administrative workarounds.

Correctional staff culture and institutional inertia also remain significant obstacles. As Keramet Reiter and others have shown, solitary confinement is deeply embedded in correctional routines and is often seen by staff as essential for maintaining order and safety. Changing this culture requires new policies and ongoing training, leadership, and incentives for staff to adopt alternative approaches.

The Role of Advocacy and Litigation

Sustained advocacy and strategic litigation have been critical drivers of solitary confinement reform. Organizations like ACLU Delaware, Southern Poverty Law Center, and Youth First Initiative have successfully challenged solitary practices in court, secured legislative victories, and kept the issue in the public eye. Grassroots advocacy, coalition-building, and media coverage have all played vital roles in pushing for reforms and holding officials accountable.

However, as the ACLU Delaware notes, lasting change will require legislative and judicial action, a shift in institutional culture, and buy-in from prison staff at all levels.

Data Transparency and Oversight

Transparency is essential for meaningful reform. Accurate, standardized data on solitary confinement—including demographics, duration, and outcomes—enables oversight, public accountability, and evidence-based policy. The Liman Center at Yale Law School has led calls for regular audits, independent oversight, and public reporting on restrictive housing. Without such transparency, measuring progress, identifying disparities, or holding agencies accountable for violations is difficult.

Community Engagement and Reentry Support

Supporting successful reentry for those leaving solitary confinement is crucial to reducing recidivism and breaking the cycle of isolation. Investments in housing, employment, education, and mental health services are all vital components of a holistic reform strategy. As highlighted by the Vera Institute, partnerships with community organizations can provide continuity of care, help formerly incarcerated individuals rebuild their lives, and reduce the likelihood that people will return to prison—or to solitary.

Community engagement also extends to families, who often serve as the primary support network for returning citizens. Enhanced visitation policies, family therapy, and reentry planning can strengthen these connections and promote stability.

The Impact of Solitary Confinement on Families and Communities

Solitary confinement’s reach extends far beyond prison walls. The effects ripple through families and entire communities, compounding the harm of incarceration and perpetuating cycles of trauma, instability, and disadvantage.

Emotional and Financial Toll on Families

Families of those in solitary confinement often experience profound emotional distress. Research from Solitary Watch highlights how loved ones grapple with anxiety, depression, and helplessness as they witness the psychological decline of a family member in isolation. The stigma surrounding solitary confinement can further isolate families, making it difficult to find support or understanding in their communities.

Financial hardship is also common. Maintaining contact with someone in solitary is expensive—phone calls and video visits are often costly, and travel to remote supermax facilities can be prohibitive. According to the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, families spend an average of $13,000 on court-related costs, phone calls, and visits throughout a loved one’s incarceration, with costs even higher for those in solitary confinement due to additional barriers.

Impact on Children

Children with a parent in solitary confinement are particularly vulnerable. As documented by the Prison Policy Initiative, these children are at heightened risk for anxiety, depression, and behavioral issues. Disrupting parent-child relationships can have lasting effects, including academic difficulties and increased involvement with the juvenile justice system. A 2015 study in Pediatrics found that children who experience parental incarceration are more likely to suffer from poor health, emotional challenges, and developmental delays.

Community-Level Consequences

The return of individuals who have been psychologically damaged by solitary confinement can have significant consequences for communities. Research from the Urban Institute and Vera Institute shows that people released directly from solitary are more likely to face unemployment, homelessness, and recidivism. The lack of mental health support and reentry planning for these individuals increases the likelihood that they will cycle back into the criminal justice system, perpetuating instability in already marginalized neighborhoods.

Communities with high rates of incarceration and solitary confinement often experience weakened social networks, reduced economic opportunities, and increased public health challenges. The Brookings Institution notes that the destabilization of families and neighborhoods caused by mass incarceration—including the use of solitary—contributes to intergenerational poverty and diminished civic engagement.

Intergenerational Trauma

The trauma of solitary confinement is not limited to the individual—it can be transmitted across generations. Studies cited by the National Institute of Justice show that children of formerly incarcerated parents are more likely to experience instability, academic difficulties, and involvement with the criminal justice system themselves. This intergenerational transmission of trauma is exacerbated when a parent has endured the extreme psychological stress of solitary.

Breaking this cycle requires more than just reforming solitary confinement practices. It demands investment in family support, mental health services, and community-based resources that can help children and families heal and thrive. Programs that facilitate family reunification, provide trauma-informed counseling, and support economic stability are crucial for mitigating harm and building resilience.

Intersectionality: Race, Gender, and Disability in Solitary Confinement

Solitary confinement is not experienced equally across the incarcerated population. The intersection of race, gender, disability, and sexual orientation shapes who are placed in isolation, how long they remain there, and the severity of the harm they endure. Understanding these disparities is essential for any meaningful reform.

Racial Disparities in Solitary Confinement

Black, Latino, and Indigenous prisoners are disproportionately represented in solitary confinement units, reflecting broader systemic racial disparities in the criminal justice system. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Black prisoners are significantly more likely to be placed in solitary than white prisoners, with some studies showing that Black men are placed in solitary at rates up to six times higher than their white peers. Prison Policy Initiative further reports that Latino and Indigenous people are also overrepresented in restrictive housing, a pattern that persists across many states and facilities. These disparities are often the result of biased disciplinary practices, lack of access to legal resources, and the cumulative effects of structural racism.

Gender-Specific Harms

Women in solitary confinement face unique and severe harms, particularly those who are pregnant or survivors of trauma. The ACLU has documented that isolation can exacerbate preexisting mental health issues, increase the risk of self-harm, and negatively impact pregnancy outcomes. Pregnant women in solitary are at higher risk for miscarriage, preterm birth, and inadequate prenatal care. Additionally, the majority of incarcerated women have histories of trauma or abuse, and solitary confinement can retraumatize them, leading to heightened anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

LGBTQ+ Prisoners and Protective Isolation

LGBTQ+ prisoners, especially transgender individuals, are frequently placed in solitary “for their own protection.” However, as the National Center for Transgender Equality explains, this practice often results in further victimization, exacerbating trauma and mental health crises. Transgender people in solitary are at much higher risk of depression, suicidal ideation, and denial of necessary medical care. Rather than providing safety, protective isolation often amounts to punishment for one’s identity.

Disability and Mental Illness

People with disabilities, particularly those with serious mental illness or cognitive impairments, are often placed in solitary due to a lack of appropriate mental health services or as a form of behavioral control. Solitary Watch has reported that individuals with psychiatric disabilities are vastly overrepresented in solitary units, where their conditions frequently deteriorate. The ACLU notes that isolation can worsen symptoms of psychosis, mania, and depression and is often used in lieu of treatment, violating fundamental human rights and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Addressing Disparities

Reform efforts must be intersectional, addressing how race, gender, disability, and sexual orientation intersect to shape the experience of solitary confinement. Data collection and reporting should be disaggregated by demographic factors to ensure that reforms benefit all affected populations. The Prison Policy Initiative and Bureau of Justice Statistics recommend that correctional agencies track and publish data on the demographics of those held in solitary to identify and address disparities.

As advocates and policymakers work to end the overuse of solitary confinement, centering the experiences of marginalized groups is essential for creating a system that is just and humane.

International Comparisons and Global Reform Trends

The United States is an outlier in its use of solitary confinement. While tens of thousands are held in isolation for weeks, months, or even years in U.S. prisons, many other countries have sharply limited or abolished the practice, citing overwhelming evidence of harm and international human rights concerns.

Canada: Constitutional Limits and Oversight

In Canada, the Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that indefinite solitary confinement is unconstitutional, leading to new federal regulations that limit isolation to a maximum of 15 consecutive days and require independent external oversight. The Office of the Correctional Investigator monitors compliance and advocates for further reforms. Since the ruling, Canada has reduced the use of solitary by 50%, with ongoing advocacy for even stricter limits and greater transparency.

Europe: Strict Time Limits and Human Rights Protections

European countries have adopted some of the world’s strictest limits on solitary confinement. In Germany, isolation is generally capped at 10 days, and its use is rare and subject to regular judicial review. The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly found that prolonged isolation constitutes inhuman and degrading treatment, violating the European Convention on Human Rights.

In Norway, prisons like Bastøy emphasize normalization, with prisoners living in conditions similar to the outside world. Solitary confinement is used only in extreme cases and for short durations. This approach is credited with Norway’s exceptionally low recidivism rate and minimal prison violence.

Sweden restricts solitary confinement to a maximum of 14 days, emphasizing rehabilitation, social integration, and regular mental health assessments. The Netherlands also caps solitary at 14 days, focusing on mental health and social support for those in custody.

Oceania: New Zealand and Australia

New Zealand has moved to restrict solitary confinement, especially for juveniles, with a focus on restorative justice and rehabilitation. The country’s correctional policies prioritize alternatives to isolation and require regular reviews for any use of segregation.

Australia has also implemented reforms to limit solitary, particularly for vulnerable populations such as youth and those with mental illness. Australian jurisdictions are increasingly adopting trauma-informed approaches and emphasizing community-based alternatives.

Global Human Rights Standards: The Mandela Rules

International human rights law sets clear standards for the use of solitary confinement. The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules) prohibit solitary confinement beyond 15 consecutive days and ban its use for juveniles and people with mental disabilities. The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture has called for a global ban on prolonged and indefinite solitary confinement, emphasizing that such practices can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.

Advocates and courts in the U.S. increasingly cite these standards as a model for reform, and they provide a benchmark for countries seeking to align their prison practices with international norms.

Lessons for the United States

These international examples demonstrate that it is possible to maintain safety, order, and rehabilitation in correctional systems without resorting to prolonged isolation. Countries that have embraced strict limits, independent oversight, and a focus on mental health and reintegration have seen reductions in violence, recidivism, and human rights violations. As the U.S. grapples with the legacy and ongoing reality of solitary confinement, these global models offer clear and actionable pathways for meaningful reform.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is solitary confinement?

Solitary confinement is the practice of isolating incarcerated individuals in a small cell for 22 to 24 hours a day, with minimal human contact and limited access to programs, property, or the outside world. This form of incarceration is also called “segregated housing,” “restrictive housing,” or “the hole.” For a comprehensive overview, visit Solitary Watch’s FAQ.

What does solitary confinement look like?

A typical solitary confinement cell is about the size of a parking space—usually 6 by 9 feet—and contains only a bed, toilet, and sink. The cell is often windowless, illuminated by harsh fluorescent lighting, and prisoners eat, sleep, and use the bathroom in the same space. Meals are delivered through a slot in the door, and out-of-cell time is generally limited to one hour per day, usually spent alone in a small, caged yard. Images and descriptions can be found through the Urban Institute.

What is solitary confinement like?

Life in solitary is marked by monotony, deprivation, and psychological stress. Prisoners have little to no social interaction, minimal access to reading materials or personal property, and rarely participate in educational or rehabilitative programming. Many describe the experience as a form of “living death,” with time losing meaning and mental health rapidly deteriorating. First-person accounts are available at Voices from Solitary.

How long in solitary confinement before you go crazy?

There is no precise threshold, but research shows that even a few days in solitary can cause psychological distress, and the risk of serious mental health effects increases dramatically after 15 days. The United Nations Mandela Rules define prolonged solitary confinement as torture if it lasts more than 15 consecutive days. Symptoms such as anxiety, depression, hallucinations, and paranoia can emerge quickly, as documented by Dr. Stuart Grassian.

What does the brain do inside solitary confinement?

Solitary confinement triggers profound neurobiological changes. MRI studies show that even 30 days of isolation can shrink the hippocampus, impairing memory and emotional regulation while increasing activity in the amygdala, which is linked to fear and anxiety. Chronic stress hormones flood the brain, causing lasting damage and increasing the risk of depression, aggression, and suicidal ideation.

Why is solitary confinement bad?

Solitary confinement is associated with severe psychological and physical harm. It increases the risk of suicide, self-harm, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Physically, it can lead to cardiovascular deterioration, sleep disruption, and weakened immune systems. The practice also increases recidivism and undermines public safety, as the Vera Institute of Justice detailed.

Is solitary confinement torture?

Many experts, including the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, consider prolonged solitary confinement to be a form of psychological torture, particularly when used for more than 15 days or on vulnerable populations such as juveniles or individuals with mental illness. The Mandela Rules explicitly prohibit such practices.

Is solitary confinement legal in the United States?

Solitary confinement is not categorically banned in the U.S., but its use is increasingly restricted by courts and legislatures, especially for juveniles and people with mental illness. Prolonged or indefinite solitary confinement has been found unconstitutional in several landmark cases, such as Porter v. Clarke. However, laws and practices vary widely by state and facility.

What does solitary confinement do to a person?

Solitary confinement can cause severe psychological distress, including anxiety, paranoia, hallucinations, depression, and suicidal thoughts. Physically, it can lead to hypertension, insomnia, and long-term cognitive impairment. The risk of self-harm and suicide is dramatically higher among those in solitary, as shown by Brooklyn Defender Services.

Why was Michael Cohen in solitary confinement?

Michael Cohen, the former attorney for Donald Trump, was placed in solitary confinement in 2020 while serving a federal sentence. According to The New York Times, Cohen was placed in isolation after he was seen dining at a restaurant while on medical furlough, which was deemed a violation of his release terms. His case drew attention to using solitary confinement for high-profile or nonviolent offenders and the lack of consistent standards in federal facilities.

What are the alternatives to solitary confinement?

Alternatives to solitary confinement include step-down programs, mental health treatment units, restorative justice initiatives, and incentive-based management systems. These approaches have been shown to reduce violence, improve mental health outcomes, and support rehabilitation. See the Prison Policy Initiative’s report and the Vera Institute’s recommendations for more.

How can I learn more or get help?

If you or a loved one is affected by solitary confinement, you can book an initial consultation with our team for more information, resources, and legal support.

Conclusion: Toward a More Humane Future